ဇြုံၜံက်

| Snakebite | |

|---|---|

| |

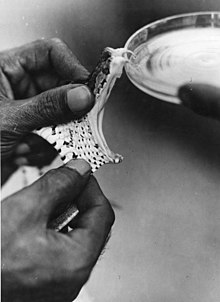

| A rattlesnake bite on the foot of a 9-year-old girl in Venezuela | |

| ဒၞာဲမလွဳ | Emergency medicine |

| လက်သန်ယဲ | Two puncture wounds, redness, swelling, severe pain at the area[၁][၂] |

| အရာမကတဵုဒှ်မာန် | Bleeding, kidney failure, severe allergic reaction, tissue death around the bite, breathing problems, amputation[၁][၃] |

| ဟိုတ်ယဲ | Snakes[၁] |

| အန္တရာယ် | Working outside with one's hands (farming, forestry, construction)[၁][၃] |

| နဲစဵုဒၞာ | Protective footwear, avoiding areas where snakes live, not handling snakes[၁] |

| နဲလွဳ | Washing the wound with soap and water, antivenom[၁][၄] |

| ၜိုတ်မဗၠးမာန် | Depends on type of snake[၅] |

| လၟိဟ်မဒှ်မာန် | Up to 5 million a year[၃] |

| စုတိ | 94,000–125,000 per year[၃] |

ဇြုံၜံက် (အၚ်္ဂလိက်: snakebite)ဂှ် ဒှ်သရ ဟိုတ်နူကဵု မဒးဒုင်ၜံက် နကဵုဇြုံ၊ ဗွဲတၟေင် မဒးဒုင်ၜံက် ကုဇြုံဂယိဂမၠိုင်။[၆] မဒးဒုင်ၜံက် ကုဇြုံဂယိတအ်မ္ဂး ဗွဲမဂၠိုင် ဂွံဆဵုကေတ် ဒၞာဲပဏေတ်သရ ၜါ နူကဵု ဂၞိဟ်ဇြုံတအ်ရ။ လဆောဝ်မ္ဂး ပဏေတ်သရ နူကဵု ဇြုံၜံက်ဂှ် ဂွံဆဵုကေတ်[၃] နကဵု မဗကေတ်ဒၟံင်၊ ဂိုဟ်ဒၟံင်၊ ကေုာံ ပ္ဍဲဒၞာဲဂှ် ဂိဒၟံင်၊ လက်သန် ဗီုဏအ် ဂွံညာတ်ကေတ်ဂှ် ကြဴနူ မဒးဒုင်ၜံက်တုဲ ဒးကေတ်အခိင် ၜိုတ်မွဲနာဍဳ။ လက်သန် ဗီုမဒးဒုင်စသိုင်တအ်မ္ဂး ဂအအ်၊ မတ်ဂၠု၊ တၞုင်ဇိုင်တၞုင်တဲ ကိတ်စ၊ ကေုာံ ပဠက်တိတ်။ ဗွဲမဂၠိုင် ဒးဒုင်ၜံက် ပ္ဍဲတဲ ဟွံသေင်မ္ဂး ပ္ဍဲဇိုင်။[၂][၇] အန္တရာယ် မကတဵုဒှ်မာန် ဟိုတ်နူ ဇြုံၜံက်ဂှ် ဗွဲမဂၠိုင် ဂြိုဟ်ယာက် ကေုာံ ဒြဟတ်ဍိုန်လျ။ ဂျိဇြုံဂှ် ပကဵု ညံင်ဆီဂွံတိတ်၊ ကောန်ကၟအ် (ကျောက်ကပ်) လီု၊ ကလိုက်ကမဵု အလ္လာဂိစ် (severe allergic reaction)၊ ပ္ဍဲပွဳပွူမဒးဒုင်ၜံက်ဂှ် ကလာပ်ရုပ်တိဿူ ချိုတ် (tissue death) ဟွံသေင်မ္ဂး ယီုဝါတ်တအ်ရ။[၁] ဟိုတ်နူဇြုံၜံက်တုဲ ဒးဒုင်ကုတ်ဇိုင်တဲ ဟွံသေင်မ္ဂး ဇိုင်တဲ မဒုင်ၜံက်တအ်ဂှ် ဟွံထတ်စောမ် မွဲအာယုက်။ ဆဂး ဂလိုင်လဵု မဒးဒုင်စဂှ် တန်တဴဒၟံင် ကုဂကူဇြုံလဵု ဇကုမဒးဒုင်ၜံက်၊ ပ္ဍဲဇကု ဒၞာဲလဵု မဒးဒုင်ၜံက်၊ ကေုာံ ဂလိုင်လဵု ဂျိဇြုံမလုပ်စိုပ် ကေုာံ ညးမဒုင်ၜံက်ဂှ် အကာဲအရာ ပရေင်ထတ်ယုက် နွံဗီုလဵုရ။[၅] ကောန်ၚာ်တအ်ဂှ် ဟိုတ်နူ ဇမၞော်ဇကုဍေဟ်တအ် ဍောတ်တုဲ အန္တရာယ်ဇၞော် နူကဵု ကဵု မၞိဟ်ဇၞော်ရ။[၈][၉]

ဇြုံတအ်ဂှ် ဍေဟ်ၜံက် ပ္ဍဲအခိင်ကာလ ဍေဟ်တအ် မဗက်ရပ်စ သတ်တၞဟ်ကီု သီုကဵု ကာလဍေဟ်တအ် မစဵုဒၞာအန္တရာယ် ဍေဟ်တအ်ရ။ ဗွဲမဂၠိုင် မဒးဒုင်ၜံက် ဟိုတ်နူမကၠောန်ကမၠောန်မ္ၚး လပှ်ဂိုင်၊ ဟွံသေင်မ္ဂး ကၠောန်ကၠအ်၊ ကၠောန်ဗ္ၚ ကေုာံ ဒၞာဲသြိုင်ခၞံတအ်ရ။ ဇြုံမနွံကဵုဂျိဂမၠိုင်ဂှ် ဇြုံဇာတ်၊ ဇြုံဗုဲ၊ ကေုာံ အဆာတ် (ဇြုံၜဳဂမၠိုင်)။ ဂကူဇြုံ ဗွဲမဂၠိုင် ဟွံမဲ ကုဂျိတုဲ ကာလဍေဟ်တအ် ရပ်စ သတ်တၞဟ်မ္ဂး ဍေဟ်တအ် တ္ၚေတ်ဂစိုတ်ကေတ်ရ။ ဇြုံဂယိတအ်ဂှ် ပါဲနူ ပ္ဍဲတိုက်အန္တာတိက တုဲ နွံဒၟံင် ဇၟာပ်တိုက်ရ။ ရံင်ပဏေတ်သရ မၜံက်လဝ်တုဲ ဂကူဇြုံလဵု မၜံက်လဝ်ဂှ် တီကေတ် ဟွံမာန်။ နကဵု ဂကောံထတ်ယုက်ဂၠးကဝ် (World Health Organization) ဟီု ဇြုံၜံက်ဂှ် "ဒှ် ပြသၞာထတ်ယုက် ညးဍုင်ကွာန် မဒးဒုင်ဝိုတ်ဒၟံင်မွဲ ပ္ဍဲကဵု ဍုင်ဒေသဂမ္တဴဂမၠိုင်" တုဲ ပ္ဍဲ သၞာံ ၂၀၁၇ စၟတ်သမ္တီ နကဵု ဂကောံထတ်ယုက်ဂၠးကဝ် ဇြုံၜံက်ဂှ် ဒှ် ယဲဒေသဂမ္တဴမဟွံစွံဂရု (Neglected Tropical Disease (Category A)) မွဲဂကူရ။ တင်ရန်တၟအ်ဂှ် တၞဟ်န ကလိဂွံ အာရီုပရေင်သုတေသန၊ သွက်ဂွံကၠောန်ပ္တိတ် ဂဥုဲအာန္တိဂယိ (ဂဥုဲဂစိုတ်ဂျိ) ကေုာံ ညံင်ဂွံလွဳလွတ် ကုညးမဒုင်ဇြုံၜံက် ပ္ဍဲကဵု ဍုင်အဃောဇၞော်မောဝ်တအ်ရ။

နဲစဵုဒၞာဲ ညံင်ဟွံဂွံဒးဒုင်ဇြုံၜံက်ဂှ် ပွမလိုန်ဒၞပ်ဍောင်၊ သအးဇ္ၚး ညံင်ဇြုံ ဟွံဂွံမံင် ပ္ဍဲကဵုဒေသ၊ ကေုာံ ဝေင်ပါဲ ပွမရပ်ဇြုံတအ်ရ။[၁] ဗီုမလွဳဂှ် တန်တဴကဵု ဂကူဇြုံ မၜံက်လဝ်ဂှ်ရ။ ကြာတ်သရ နကဵု ဍာ် ကဵု သာပ်ပျာ ကေုာံ မံင်ညိင်င်ဂှ် ဒှ်ကသပ် ခိုဟ်မွဲရ။[၄] မဂစာန်ဇြောတ်ပ္တိတ်ဂျိ၊ ကရေက်ဒၞာဲသရ နကဵုၜုန်၊ ဟွံသေင်မ္ဂး မပူဒက် ညံင်ဆီ အာကၠုင်ဟွံဂွံဂှ် ဟွံမိက်ကဵုပ။ အာန္တိဂယိ (ဝါ) ဂဥုဲဂစိုတ်ဂျိ (Antivenom) ဂှ် ဒှ်အရာမစဵုဒၞာကဵု ညံင်ဟွံဂွံဒးချိုတ် ဟိုတ်နူဇြုံၜံက်၊ ဆဂး ဂဥုဲဂစိုတ်ဂျိတအ်ဂှ် နွံကဵု အာနိသံသပရေအ်ပရေအ်။[၃][၁၀] ဇြုံမွဲကုမွဲ ဂကူဂျိ ဟွံတုပ်ရေင်သကအ်တုဲ ဂဥုဲအာန္တိဂယိ (ဝါ) ဂဥုဲဂစိုတ်ဂျိလေဝ် ဒးစကာ ဟွံတုပ်ရေင်သကအ်ပၠန်ရ။ ယဝ်ရ ဟွံတီဂကူဇြုံမ္ဂး ရံင်ကဵုဒေသဂှ် ဇြုံဂယိ ဂကူလဵု မနွံစဂၠိုင် ချပ်ကေတ်တုဲ ဆိင်ကဵုဂဥုဲရ။ ပ္ဍဲဒေသလ္ၚဵု ဂကူဇြုံဂယိ နွံနာနာသာ်တုဲ ဂဥုဲဂစိုတ်ဂျိလဵု ဂွံကဵုဂှ် ဖန်စဝါတ်တုဲ လွဳဟွံဒးနွံကီုရ။

လၟိဟ်မၞိဟ် မဒးဒုင်ၜံက် ကုဇြုံဂယိ ပ္ဍဲဂၠးတိဏအ် ပ္ဍဲမွဲမွဲသၞာံ စိုပ်စဵုကဵု မၞိဟ် မသုန် မဳလဳယာန်မာန်ရ။[၃] မၞိဟ်ၜိုတ် ၂.၅ မဳလဳယာန်ဂှ် ဒးဂျိတုဲ ပ္ဍဲဂှ် မၞိဟ် အကြာ ၂၀.၀၀၀ ကဵု ၁၂၅.၀၀၀ ဂှ် ဒးချိုတ် နကဵုဇြုံၜံက်ရ။ ပ္ဍဲဂၠးတိဏအ် မွဲဒေသကဵု မွဲဒေသ ကတဵုဒှ်စ ဟွံတုပ်ရေင်သကအ်ရ။[၁၁] ဒၞာဲဒေသ မကတဵုဒှ်စဂၠိုင်အိုတ်ဂှ် ဒှ်တိုက်အာဖရိက၊ အာရှ၊ ကေုာံ လေတ္တေန် အမေရိကာ ပ္ဍဲကဵု ဒေသကွာန်ဂြိုပ်ဂမၠိုင်ရ။[၉] လၟိဟ်မၞိဟ်မချိုတ် နကဵုဇြုံၜံက် ပ္ဍဲတိုက် သြသတြေလျ၊ ဥရောပ ကေုာံ အမေရိကသၟဝ်ကျာတအ်ဂှ် အောန်ကွေဟ်ဟ်ရ။[၁၀][၁၂] ဥပမာ ပ္ဍဲရးနိဂီုပံင်ကောံအမေရိကာန် မွဲမွဲသၞာံ မၞိဟ်မဒးဒုင်ၜံက် ဇြုံဂယိ နွံ အကြာ ထပှ် ကဵု ဒစာံလ္ၚီကီုလေဝ် မၞိဟ်မဒးချိုတ် နကဵုဇြုံၜံက်ဂှ် နွံဆ မၞိဟ်မသုန်ဓဝ် (မၞိဟ် ၆၅ မဳလဳယာန် မၞိဟ်မွဲ)။[၁]

သင်္ကေတ ကေုာံ လက်သန်ယဲ

[ပလေဝ်ဒါန် | ပလေဝ်ဒါန် တမ်ကၞက်]

လက်သန်ယဲ မလေပ်ကတဵုဒှ်မာန် ဟိုတ်နူဇြုံၜံက်ဂှ် မပ္တံကဵု စံင်ပရံင် ကေုာံ ဂအအ် (nausea and vomiting)၊ ဂၞဴအာ (diarrhea)၊ ဗၜူ (vertigo)၊ ဒြဟတ်အိုတ် (fainting)၊ ဂြိုဟ်ယာ် (tachycardia) ကေုာံ ဂံက် (cold)၊ ပဠက်တိတ် (clammy skin)။[၂][၁၃]လက်သန်ယဲဂှ် တန်တဴဒၟံင် ဂကူဇြုံ၊ ဒးဒုင်ၜံက် ကုဂကူဇြုံတၞဟ်ခြာမ္ဂး လက်သန်ယဲလေဝ် ထ္ၜးတၞဟ်ခြာကီုရ။

ဇြုံဂယိ ဟွံသေင် (ဝါ) ဇြုံဂျိဟွံမဲ ၜံက်ဒးလေဝ် မလေပ်ပကဵု ညံင်ဂွံဒှ်သရမာန်ကီုရ။ ဒၞာဲမဒးဒုင်ၜံက်ဂှ် စၟလုပ်ဂွံတုဲ ဒှ်သရ။ လဆောဝ်မ္ဂး စၟဗက်တဳရဳယာ မပတံကဵု Clostridium tetani တအ် လုပ်ကၠောအ်ဂွံတုဲ ဒှ်သရ။ မပ္တံကဵု ဂိုဟ်၊ ဒှ်သရဇၞော်ဇၞော်မာန်ကီုရ။

ဇြုံၜံက်ဒှ်မ္ဂး ဂကူဇြုံနွံကဵုဂျိ ကဵုဒှ် ဟွံမဲကုဂျိကဵုဒှ် ဒၞာဲမဒးဒုင်ၜံက်ဂှ် မပ္တံကဵု ဍာဲတိုန် ဂိသကေဝ်တအ် မလေပ်ကတဵုဒှ်သၟးရ။[၂] ယဝ်ရ ဒးဒုင်ၜံက် နကဵု ဇြုံဗုဲ (vipers) ကဵု ဇြုံဇာတ် (cobras)မ္ဂး ဂိကွေဟ်ဟ်တုဲ ကလာပ်ရုပ်တိဿူ ပ္ဍဲဒၞာဲမဒးဒုင်ၜံက်ဂှ် ဂိအိုတ်အစောန် ဒးညိဟွံဂွံ၊ တုဲပၠန် ဂိုဟ်တိုန် ဗွဲမဂၠိုင် အပ္ဍဲမသုန်မိနေတ်ဂှ်။[၁၀]ပ္ဍဲဒၞာဲဂှ် သီုကဵု ဆီတိတ် ကေုာံ ဍာ်သရတိတ်၊ ကလာပ်ရုပ်တိဿူချိုတ်။ လက်သန် မကတဵုဒှ် ပ္ဍဲအခိင်ကိုပ်ကၠာ ဒၞာဲဂၞိဟ်ဇြုံဗုဲ ကေုာံ ဇြုံဗုဲၜံက်မ္ဂး လက်သန် မပ္တံကဵု ဒြဟတ်အိုတ် (lethargy)၊ bleeding (ဆီတိတ်)၊ ဍောင် (weakness)၊ စံင်ပရံင် (nausea) ကေုာံ ဂအအ် (vomiting)။ လက်သန် မကတဵုဒှ် အခိင်လအ်ညိဂှ် ဒှ် မပ္တံကဵု အသိင်ဆီဒြေပ်ဍိုန်လျ (hypotension)၊ ယီုဝါတ် (tachypnea)၊ ဂြိုဟ်ယာ်ထတ် (severe tachycardia)၊ ဆီတိတ်ဗွဲအပ္ဍဲ ဗွဲမဂၠိုင် (severe internal bleeding)၊ (altered sensorium)၊ ကောန်ကၟအ်လီု (kidney failure)၊ ကေုာံ ယဓီုကျာလီု (respiratory failure)။

ယဝ်ရ မဒးဒုင်ၜံက် နကဵုဇြုံဂကူလ္ၚဵု မပ္တံကဵု ဇြုံ (ဂျက်မြွေ) (kraits)၊ ဇြုံ (coral snake)၊ ဇြုံ (Mojave rattlesnake)၊ ကေုာံ ဇြုံ (the speckled rattlesnake)တအ်မ္ဂး ၜိုန်ရ ဂျိဍေဟ်တအ် ပကဵု အန္တရာယ်လမျီုကီုလေဝ် ဒးဒုင်စသိုင် ညိည ဟွံသေင်မ္ဂး ညိဟွံဂိရ။[၂] ညးလ္ၚဵုလဴထ္ၜး ပရေင်ဆဵုဂဗညးတအ် အခိင်ညးတအ် မဒးဒုင်ၜံက် နကဵုဂကူဇြုံ rattlesnake ဂှ် ညးတအ် ဂွံဒုင်စသိုင် တံင်ဂြဲဒၟံင် ("rubbery")၊ ခလာန် ("minty") ဟွံသေင်မ္ဂး မဇြိုင်ဒၟံင် ("metallic")။ ဂျိဇြုံဇာတ် ကေုာံ ဇြုံRinkhals တအ်ဂှ် လုပ်စိုပ် ပ္ဍဲဇကုပိုယ်တုဲ ကသိုဟ်တိတ် ဂၠံင်မတ် ညးမဒးဒုင်ၜံက်။ အရာဏအ်ဂှ် ပကဵု ညံင်မတ်ဂွံဂိမွဲတဲဓဝ်၊ မတ်ကၠု (ophthalmoparesis) ကေုာံ လဆောဝ်မ္ဂး မတ်ကၠက်။

ယဝ်ရ ဒးဒုင်ၜံက် နကဵု ဂကူဇြုံ Australian elapids ကဵု ဂကူဇြုံဗုဲ ဗွဲမဂၠိုင်မ္ဂး ဂျိဍေဟ် ပကဵု ညံင်ဂွံ ဆီတိတ် ဗွဲအပ္ဍဲ (coagulopathy)၊ လဆောဝ်မ္ဂး ဂွံဆဵုကေတ် ဆီဇွောဝ်တိတ် ဂၠံင်ပါင် ဂၠံင်မုဟ်။[၁၀] အဝဲအင်္ဂအပ္ဍဲ ဆီတိတ်၊ သီုကဵု က္ဍဟ် ကေုာံ ကြုတ်ဂမၠိုင်၊ ကေုာံ ကေုာံစၞာံဂမၠိုင်လေဝ် သရိုဟ်လီုနွံကီုရ။

ဂျိဇြုံ မပ္တံကဵု sea snakes, kraits, cobras, king cobra, mambas, ကေုာံ many Australian species တအ်ဂှ် နွံကဵု ဂျိ မပလီုကဵု သၞောတ်ကတေင်အာရီုတုဲ ပကဵု ညံင်ကတေင်အာရီုဂမၠိုင်ဂွံလီု ဟွံကၠောန်ကမၠောန်ရ။[၂][၁၀][၁၄] The person may present with strange disturbances to their vision, including blurriness. Paresthesia throughout the body, as well as difficulty in speaking and breathing, may be reported. Nervous system problems will cause a huge array of symptoms, and those provided here are not exhaustive. If not treated immediately they may die from respiratory failure.

Venom emitted from some types of cobras, almost all vipers and some sea snakes causes necrosis of muscle tissue. Muscle tissue will begin to die throughout the body, a condition known as rhabdomyolysis. Rhabdomyolysis can result in damage to the kidneys as a result of myoglobin accumulation in the renal tubules. This, coupled with hypotension, can lead to acute kidney injury, and, if left untreated, eventually death.

Snakebite is also known to cause depression and post-traumatic stress disorder in a high proportion of people who survive.[၁၅]

Cause

[ပလေဝ်ဒါန် | ပလေဝ်ဒါန် တမ်ကၞက်]In the developing world most snakebites occur in those who work outside such as farmers, hunters, and fishermen. They often happen when a person steps on the snake or approaches it too closely. In the United States and Europe snakebites most commonly occur in those who keep them as pets.[၁၆]

The type of snake that most often delivers serious bites depends on the region of the world. In Africa, it is mambas, Egyptian cobras, puff adders, and carpet vipers. In the Middle East, it is carpet vipers and elapids. In Latin America, it is snakes of the Bothrops and Crotalus types, the latter including rattlesnakes.[၁၆] In North America, rattlesnakes are the primary concern, and up to 95% of all snakebite-related deaths in the United States are attributed to the western and eastern diamondback rattlesnakes.[၂] In South Asia, it was previously believed that Indian cobras, common kraits, Russell's viper, and carpet vipers were the most dangerous; other snakes, however, may also cause significant problems in this area of the world.

Pathophysiology

[ပလေဝ်ဒါန် | ပလေဝ်ဒါန် တမ်ကၞက်]Since envenomation is completely voluntary, all venomous snakes are capable of biting without injecting venom into a person. Snakes may deliver such a "dry bite" rather than waste their venom on a creature too large for them to eat, a behaviour called venom metering.[၁၇] However, the percentage of dry bites varies among species: 80 percent of bites inflicted by sea snakes, which are normally timid, do not result in envenomation,[၁၄] whereas only 25 percent of pit viper bites are dry.[၂] Furthermore, some snake genera, such as rattlesnakes, significantly increase the amount of venom injected in defensive bites compared to predatory strikes.[၁၈]

Some dry bites may also be the result of imprecise timing on the snake's part, as venom may be prematurely released before the fangs have penetrated the person. Even without venom, some snakes, particularly large constrictors such as those belonging to the Boidae and Pythonidae families, can deliver damaging bites; large specimens often cause severe lacerations, or the snake itself pulls away, causing the flesh to be torn by the needle-sharp recurved teeth embedded in the person. While not as life-threatening as a bite from a venomous species, the bite can be at least temporarily debilitating and could lead to dangerous infections if improperly dealt with.

While most snakes must open their mouths before biting, African and Middle Eastern snakes belonging to the family Atractaspididae are able to fold their fangs to the side of their head without opening their mouth and jab a person.[၁၉]

Snake venom

[ပလေဝ်ဒါန် | ပလေဝ်ဒါန် တမ်ကၞက်]It has been suggested that snakes evolved the mechanisms necessary for venom formation and delivery sometime during the Miocene epoch.[၂၀] During the mid-Tertiary, most snakes were large ambush predators belonging to the superfamily Henophidia, which use constriction to kill their prey. As open grasslands replaced forested areas in parts of the world, some snake families evolved to become smaller and thus more agile. However, subduing and killing prey became more difficult for the smaller snakes, leading to the evolution of snake venom. Other research on Toxicofera, a hypothetical clade thought to be ancestral to most living reptiles, suggests an earlier time frame for the evolution of snake venom, possibly to the order of tens of millions of years, during the Late Cretaceous.[၂၁]

Snake venom is produced in modified parotid glands normally responsible for secreting saliva. It is stored in structures called alveoli behind the animal's eyes, and ejected voluntarily through its hollow tubular fangs. Venom is composed of hundreds to thousands of different proteins and enzymes, all serving a variety of purposes, such as interfering with a prey's cardiac system or increasing tissue permeability so that venom is absorbed faster.

Venom in many snakes, such as pit vipers, affects virtually every organ system in the human body and can be a combination of many toxins, including cytotoxins, hemotoxins, neurotoxins, and myotoxins, allowing for an enormous variety of symptoms.[၂][၂၂] Earlier, the venom of a particular snake was considered to be one kind only, i.e. either hemotoxic or neurotoxic, and this erroneous belief may still persist wherever the updated literature is hard to access. Although there is much known about the protein compositions of venoms from Asian and American snakes, comparatively little is known of Australian snakes.

The strength of venom differs markedly between species and even more so between families, as measured by median lethal dose (LD50) in mice. Subcutaneous LD50 varies by over 140-fold within elapids and by more than 100-fold in vipers. The amount of venom produced also differs among species, with the Gaboon viper able to potentially deliver from 450–600 milligrams of venom in a single bite, the most of any snake.[၂၃] Opisthoglyphous colubrids have venom ranging from life-threatening (in the case of the boomslang) to barely noticeable (as in Tantilla).

Prevention

[ပလေဝ်ဒါန် | ပလေဝ်ဒါန် တမ်ကၞက်]

Snakes are most likely to bite when they feel threatened, are startled, are provoked, or when they have been cornered. Snakes are likely to approach residential areas when attracted by prey, such as rodents. Regular pest control can reduce the threat of snakes considerably. It is beneficial to know the species of snake that are common in local areas, or while travelling or hiking. Africa, Australia, the Neotropics, and southern Asia in particular are populated by many dangerous species of snake. Being aware of—and ultimately avoiding—areas known to be heavily populated by dangerous snakes is strongly recommended.[နွံပၟိက် ဗၟံက်ထ္ၜးတင်နိဿဲ]

When in the wilderness, treading heavily creates ground vibrations and noise, which will often cause snakes to flee from the area. However, this generally only applies to vipers, as some larger and more aggressive snakes in other parts of the world, such as mambas and cobras,[၂၄] will respond more aggressively. If presented with a direct encounter, it is best to remain silent and motionless. If the snake has not yet fled, it is important to step away slowly and cautiously.

The use of a flashlight when engaged in camping activities, such as gathering firewood at night, can be helpful. Snakes may also be unusually active during especially warm nights when ambient temperatures exceed 21 °C (70 °F). It is advised not to reach blindly into hollow logs, flip over large rocks, and enter old cabins or other potential snake hiding-places. When rock climbing, it is not safe to grab ledges or crevices without examining them first, as snakes are cold-blooded and often sunbathe atop rock ledges.

In the United States, more than 40 percent of people bitten by snake intentionally put themselves in harm's way by attempting to capture wild snakes or by carelessly handling their dangerous pets—40 percent of that number had a blood alcohol level of 0.1 percent or more.[၂၅]

It is also important to avoid snakes that appear to be dead, as some species will actually roll over on their backs and stick out their tongue to fool potential threats. A snake's detached head can immediately act by reflex and potentially bite. The induced bite can be just as severe as that of a live snake.[၂][၂၆] As a dead snake is incapable of regulating the venom injected, a bite from a dead snake can often contain large amounts of venom.[၂၇]

Treatment

[ပလေဝ်ဒါန် | ပလေဝ်ဒါန် တမ်ကၞက်]It may be difficult to determine if a bite by any species of snake is life-threatening. A bite by a North American copperhead on the ankle is usually a moderate injury to a healthy adult, but a bite to a child's abdomen or face by the same snake may be fatal. The outcome of all snakebites depends on a multitude of factors: the type of snake, the size, physical condition, and temperature of the snake, the age and physical condition of the person, the area and tissue bitten (e.g., foot, torso, vein or muscle), the amount of venom injected, the time it takes for the person to find treatment, and finally the quality of that treatment.[၂][၂၈] An overview of systematic reviews on different aspects of snakebite management found that the evidence base from majority of treatment modalities is low quality.[၂၉]

Snake identification

[ပလေဝ်ဒါန် | ပလေဝ်ဒါန် တမ်ကၞက်]Identification of the snake is important in planning treatment in certain areas of the world, but is not always possible. Ideally the dead snake would be brought in with the person, but in areas where snake bite is more common, local knowledge may be sufficient to recognize the snake. However, in regions where polyvalent antivenoms are available, such as North America, identification of snake is not a high priority item. Attempting to catch or kill the offending snake also puts one at risk for re-envenomation or creating a second person bitten, and generally is not recommended.

The three types of venomous snakes that cause the majority of major clinical problems are vipers, kraits, and cobras. Knowledge of what species are present locally can be crucial, as is knowledge of typical signs and symptoms of envenomation by each type of snake. A scoring system can be used to try to determine the biting snake based on clinical features,[၃၀] but these scoring systems are extremely specific to particular geographical areas.

First aid

[ပလေဝ်ဒါန် | ပလေဝ်ဒါန် တမ်ကၞက်]Snakebite first aid recommendations vary, in part because different snakes have different types of venom. Some have little local effect, but life-threatening systemic effects, in which case containing the venom in the region of the bite by pressure immobilization is desirable. Other venoms instigate localized tissue damage around the bitten area, and immobilization may increase the severity of the damage in this area, but also reduce the total area affected; whether this trade-off is desirable remains a point of controversy. Because snakes vary from one country to another, first aid methods also vary.

Many organizations, including the American Medical Association and American Red Cross, recommend washing the bite with soap and water. Australian recommendations for snake bite treatment recommend against cleaning the wound. Traces of venom left on the skin/bandages from the strike can be used in combination with a snake bite identification kit to identify the species of snake. This speeds determination of which antivenom to administer in the emergency room.[၃၁]

Pressure immobilization

[ပလေဝ်ဒါန် | ပလေဝ်ဒါန် တမ်ကၞက်]

As of 2008, clinical evidence for pressure immobilization via the use of an elastic bandage is limited.[၃၂] It is recommended for snakebites that have occurred in Australia (due to elapids which are neurotoxic).[၃၃] It is not recommended for bites from non-neurotoxic snakes such as those found in North America and other regions of the world.[၃၄] The British military recommends pressure immobilization in all cases where the type of snake is unknown.[၃၅]

The object of pressure immobilization is to contain venom within a bitten limb and prevent it from moving through the lymphatic system to the vital organs. This therapy has two components: pressure to prevent lymphatic drainage, and immobilization of the bitten limb to prevent the pumping action of the skeletal muscles.

Antivenom

[ပလေဝ်ဒါန် | ပလေဝ်ဒါန် တမ်ကၞက်]Until the advent of antivenom, bites from some species of snake were almost universally fatal.[၃၆] Despite huge advances in emergency therapy, antivenom is often still the only effective treatment for envenomation. The first antivenom was developed in 1895 by French physician Albert Calmette for the treatment of Indian cobra bites. Antivenom is made by injecting a small amount of venom into an animal (usually a horse or sheep) to initiate an immune system response. The resulting antibodies are then harvested from the animal's blood.

Antivenom is injected into the person intravenously, and works by binding to and neutralizing venom enzymes. It cannot undo damage already caused by venom, so antivenom treatment should be sought as soon as possible. Modern antivenoms are usually polyvalent, making them effective against the venom of numerous snake species. Pharmaceutical companies which produce antivenom target their products against the species native to a particular area. Although some people may develop serious adverse reactions to antivenom, such as anaphylaxis, in emergency situations this is usually treatable and hence the benefit outweighs the potential consequences of not using antivenom. Giving adrenaline (epinephrine) to prevent adverse reactions to antivenom before they occur might be reasonable in cases where they occur commonly. Antihistamines do not appear to provide any benefit in preventing adverse reactions.

Outmoded

[ပလေဝ်ဒါန် | ပလေဝ်ဒါန် တမ်ကၞက်]

The following treatments, while once recommended, are considered of no use or harmful, including tourniquets, incisions, suction, application of cold, and application of electricity.[၃၄] Cases in which these treatments appear to work may be the result of dry bites.

- Application of a tourniquet to the bitten limb is generally not recommended. There is no convincing evidence that it is an effective first-aid tool as ordinarily applied.[၃၇] Tourniquets have been found to be completely ineffective in the treatment of Crotalus durissus bites,[၃၈] but some positive results have been seen with properly applied tourniquets for cobra venom in the Philippines.[၃၉] Uninformed tourniquet use is dangerous, since reducing or cutting off circulation can lead to gangrene, which can be fatal. The use of a compression bandage is generally as effective, and much safer.

- Cutting open the bitten area, an action often taken prior to suction, is not recommended since it causes further damage and increases the risk of infection; the subsequent cauterization of the area with fire or silver nitrate (also known as infernal stone) is also potentially threatening.[၄၀]

- Sucking out venom, either by mouth or with a pump, does not work and may harm the affected area directly.[၄၁] Suction started after three minutes removes a clinically insignificant quantity—less than one-thousandth of the venom injected—as shown in a human study.[၄၂] In a study with pigs, suction not only caused no improvement but led to necrosis in the suctioned area.[၄၃] Suctioning by mouth presents a risk of further poisoning through the mouth's mucous tissues. The helper may also release bacteria into the person's wound, leading to infection.

- Immersion in warm water or sour milk, followed by the application of snake-stones (also known as la Pierre Noire), which are believed to draw off the poison in much the way a sponge soaks up water.

- Application of a one-percent solution of potassium permanganate or chromic acid to the cut, exposed area. The latter substance is notably toxic and carcinogenic.

- Drinking abundant quantities of alcohol following the cauterization or disinfection of the wound area.

- Use of electroshock therapy in animal tests has shown this treatment to be useless and potentially dangerous.[၄၄][၄၅][၄၆][၄၇]

In extreme cases, in remote areas, all of these misguided attempts at treatment have resulted in injuries far worse than an otherwise mild to moderate snakebite. In worst-case scenarios, thoroughly constricting tourniquets have been applied to bitten limbs, completely shutting off blood flow to the area. By the time the person finally reached appropriate medical facilities their limbs had to be amputated.

Epidemiology

[ပလေဝ်ဒါန် | ပလေဝ်ဒါန် တမ်ကၞက်]Estimates vary from 1.2 to 5.5 million snakebites, 421,000 to 2.5 million envenomings, and 20,000 to 125,000 deaths.[၃][၁၁] Since reporting is not mandatory in much of the world, the data on the frequency of snakebites is not precise. Many people who survive bites have permanent tissue damage caused by venom, leading to disability.[၁၀] Most snake envenomings and fatalities occur in South Asia, Southeast Asia, and sub-Saharan Africa, with India reporting the most snakebite deaths of any country.

Most snakebites are caused by non-venomous snakes. Of the roughly 3,000 known species of snake found worldwide, only 15% are considered dangerous to humans.[၂][၁၁] Snakes are found on every continent except Antarctica. The most diverse and widely distributed snake family, the colubrids, has approximately 700 venomous species,[၄၈] but only five genera—boomslangs, twig snakes, keelback snakes, green snakes, and slender snakes—have caused human fatalities.

Worldwide, snakebites occur most frequently in the summer season when snakes are active and humans are outdoors.[၁၁][၄၉] Agricultural and tropical regions report more snakebites than anywhere else.[၅၀] In the United States, those bitten are typically male and between 17 and 27 years of age.[၂][၅၁] Children and the elderly are the most likely to die.[၂၈]

References

[ပလေဝ်ဒါန် | ပလေဝ်ဒါန် တမ်ကၞက်]- ↑ ၁.၀ ၁.၁ ၁.၂ ၁.၃ ၁.၄ ၁.၅ ၁.၆ ၁.၇ ၁.၈ Venomous Snakes.

- ↑ ၂.၀၀ ၂.၀၁ ၂.၀၂ ၂.၀၃ ၂.၀၄ ၂.၀၅ ၂.၀၆ ၂.၀၇ ၂.၀၈ ၂.၀၉ ၂.၁၀ ၂.၁၁ ၂.၁၂ "Bites of venomous snakes" .

- ↑ ၃.၀ ၃.၁ ၃.၂ ၃.၃ ၃.၄ ၃.၅ ၃.၆ ၃.၇ Animal bites: Fact sheet N°373.

- ↑ ၄.၀ ၄.၁ Neglected tropical diseases: Snakebite. World Health Organization. Archived from the original on 2015-09-30။ Retrieved on 2021-01-15။. World Health Organization. Archived from the original on 30 September 2015. Retrieved 19 May 2015.

- ↑ ၅.၀ ၅.၁ Rosen's emergency medicine : concepts and clinical practice။

- ↑ Definition of Snakebite (in en).

- ↑ "Venomous snakebites." .

- ↑ World Report on Child Injury Prevention (in en)။

- ↑ ၉.၀ ၉.၁ Snake antivenoms: Fact sheet N°337.

- ↑ ၁၀.၀ ၁၀.၁ ၁၀.၂ ၁၀.၃ ၁၀.၄ ၁၀.၅ "Trends in Snakebite Envenomation Therapy: Scientific, Technological and Public Health Considerations" .

- ↑ ၁၁.၀ ၁၁.၁ ၁၁.၂ ၁၁.၃ "The global burden of snakebite: a literature analysis and modelling based on regional estimates of envenoming and deaths" (4 November 2008).Kasturiratne, A.; Wickremasinghe, A. R.; de Silva, N; Gunawardena, NK; Pathmeswaran, A; Premaratna, R; Savioli, L; Lalloo, DG; de Silva, HJ (4 November 2008). "The global burden of snakebite: a literature analysis and modelling based on regional estimates of envenoming and deaths". PLOS Medicine. 5 (11): e218. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.0050218. PMC 2577696. PMID 18986210.

- ↑ "Snake-bites: appraisal of the global situation" .

- ↑ "Envenomation by the Eastern coral snake (Micrurus fulvius fulvius). A study of 39 victims" . JAMA 258 (12): 1615–18. doi:. PMID 3625968.

- ↑ ၁၄.၀ ၁၄.၁ Phillips, Charles M.. "Sea snake envenomation". Dermatologic Therapy 15 (1): 58–61(4). doi:.

- ↑ "Citation is missing a title. Either specify one, or click here and a bot will try to complete the citation details for you. {{{title}}}" (November 2020).

- ↑ ၁၆.၀ ၁၆.၁ Brutto, edited by Hector H. Garcia, Herbert B. Tanowitz, Oscar H. Del (2013). Neuroparasitology and tropical neurology, 351. ISBN 9780444534996။

- ↑ Young, Bruce A. (2002). "Do Snakes Meter Venom?". BioScience 52 (12): 1121–26. doi:.

- ↑ Young, Bruce A. (2001). "Venom flow in rattlesnakes: mechanics and metering". The Journal of Experimental Biology 204 (Pt 24): 4345–4351. PMID 11815658.

- ↑ Deufel, Alexandra (2003). "Feeding in Atractaspis (Serpentes: Atractaspididae): a study in conflicting functional constraints". Zoology 106 (1): 43–61. doi:. PMID 16351890.

- ↑ Jackson, Kate (2003). "The evolution of venom-delivery systems in snakes". Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society 137 (3): 337–354. doi:.

- ↑ "Early evolution of the venom system in lizards and snakes" (2006). Nature 439 (7076): 584–8. doi:. Archived ၂၀၀၉-၀၅-၃၀ at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ Russell, Findlay E.. "Snake Venom Poisoning in the United States". Annual Review of Medicine 31: 247–59. doi:. PMID 6994610.

- ↑ Spawls, Stephen. The Dangerous Snakes of Africa။

- ↑ Haji, R.. Venomous snakes and snake bites. Archived from the original on 2012-04-25။ Retrieved on 2021-01-15။

- ↑ "Venomous snakebites in the United States" : 386–92.

- ↑ "Venomous snakebites. Current concepts in diagnosis, treatment, and management" (1992). Emerg Med Clin North Am 10 (2): 249–67. PMID 1559468.

- ↑ Suchard, JR (1999). "Envenomations by Rattlesnakes Thought to Be Dead". The New England Journal of Medicine 340 (24). doi:. PMID 10375322.

- ↑ ၂၈.၀ ၂၈.၁ "Snake venom poisoning in the United States: a review of therapeutic practice" . South. Med. J. 87 (6): 579–89. doi:. PMID 8202764.

- ↑ Bhaumik, Soumyadeep (October 2020). "Interventions for the management of snakebite envenoming: An overview of systematic reviews". PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases 14 (10): e0008727. doi:. PMID 33048936.

- ↑ "Identifying the biting species in snakebite by clinical features: an epidemiological tool for community surveys" (2006). Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg 100 (9): 874–8. doi:. PMID 16412486.

- ↑ Chris Thompson. Treatment of Australian Snake Bites.

- ↑ Currie, Bart J. (2008). "Effectiveness of pressure-immobilization first aid for snakebite requires further study". Emergency Medicine Australasia 20 (3): 267–270(4). doi:. PMID 18549384.

- ↑ Patrick Walker, J. "Venomous bites and stings". Current Problems in Surgery 50 (1): 9–44. doi:. PMID 23244230.

- ↑ ၃၄.၀ ၃၄.၁ "Pressure immobilization after North American Crotalinae snake envenomation" . Journal of Medical Toxicology 7 (4): 322–3. doi:. PMID 22065370.

- ↑ Wall, C. "British Military snake-bite guidelines: pressure immobilisation". Journal of the Royal Army Medical Corps 158 (3): 194–8. doi:. PMID 23472565.

- ↑ You must specify title = and url = when using {{cite web}}..

- ↑ Theakston RD. "An objective approach to antivenom therapy and assessment of first-aid measures in snake bite".

- ↑ "Tourniquet ineffectiveness to reduce the severity of envenoming after Crotalus durissus snake bite in Belo Horizonte, Minas Gerais, Brazil" .

- ↑ "Tourniquet application after cobra bite: delay in the onset of neurotoxicity and the dangers of sudden release" .

- ↑ Lupano. Corso di Scienze Naturali a uso delle Scuole Complementari။

- ↑ "Images in emergency medicine. Skin damage following application of suction device for snakebite" .

- ↑ "Suction for venomous snakebite: a study of "mock venom" extraction in a human model" .

- ↑ "Effects of a negative pressure venom extraction device (Extractor) on local tissue injury after artificial rattlesnake envenomation in a porcine model" .

- ↑ Russell F. "Another warning about electric shock for snakebite".

- ↑ Ryan A. "Don't use electric shock for snakebite".

- ↑ "Electric shock does not save snakebitten rats" .

- ↑ "Electric shocks are ineffective in treatment of lethal effects of rattlesnake envenomation in mice" .

- ↑ Mackessy, Stephen P. (2002). "Biochemistry and pharmacology of colubrid snake venoms". Journal of Toxicology: Toxin Reviews 21 (1–2): 43–83. doi:.

- ↑ "Rattlesnake Bites in Southern California and Rationale for Recommended Treatment" (1 January 1988). West J Med 148 (1): 37–44. PMID 3277335.

- ↑ Gutiérrez, José María (6 June 2006). "Confronting the Neglected Problem of Snake Bite Envenoming: The Need for a Global Partnership". PLOS Medicine 3 (6): e150. doi:. PMID 16729843.

- ↑ Parrish H. "Incidence of treated snakebites in the United States". Public Health Rep 81 (3): 269–76. doi:. PMID 4956000.

- Bibliography

Further reading

[ပလေဝ်ဒါန် | ပလေဝ်ဒါန် တမ်ကၞက်]

External links

[ပလေဝ်ဒါန် | ပလေဝ်ဒါန် တမ်ကၞက်]- WHO Snake Antivenoms Database

- Organization. Guidelines for the management of snakebites။

- Webarchive template wayback links

- Articles with broken citations

- Pages using PMID magic links

- Pages using ISBN magic links

- All articles with unsourced statements

- Articles with unsourced statements from July 2020

- Articles with invalid date parameter in template

- ပရေင်ထတ်ယုက်

- ပြန်လည်မဆန်းစစ်ရသေးသော ဘာသာပြန်များပါဝင်သည့် စာမျက်နှာများ